This is what happened. I took my first trip to China in October, 1996 to stay with friends, Don and Loretta Gibbs, currently on assignment at Peking University where he is running the Education Abroad Program for the University of California.

I met up with them in Hong Kong. They were at the tail end of a trip to South China and we were returning to Beijing together.

After two full days in Hong Kong, I was ready to move on to the mainland. Hong Kong's main claim to fame seems to be its beautiful malls and whom among us hasn't seen too many malls?

Most people fly to their destinations on the mainland but it was Don's idea to relax and take a slow boat to China. We bought first class tickets (US $63) for the overnight voyage and boarded the Jimei, a ship purchased from Norway many, many years ago. As we steamed out of the Hong Kong harbor we had plenty of time to admire the skyline and congratulate ourselves on rediscovering this civilized way of traveling.

The sea was calm, the weather clear, and the ship was not crowded. The overnight trip to Xiamen was uneventful, in fact, I found it downright soporific. The gentle pitch and roll of the ship made me sleepy, while Don and Loretta decided to dance in the lounge. While the lounge had a number of chain-smoking Chinese men traveling alone, no one else danced. They preferred to stare at Don and Loretta.

I went down to my cabin, fell asleep with my clothes on and didn't wake until the morning. I looked out the porthole and was excited to see tiny fishing vessels and, far in the distance, land.

I met Don and Loretta for a breakfast of salty pickles, peanuts, dried shrimp, tiny egg rolls, rice gruel, tea. Don raved about the trip. Sure, the ship had seen better days and the upkeep was lacking, but it still beat taking an airplane.

"And my shower this morning was just great," he said.

"You took a shower?" I asked. A shower would have been wonderful, but there were no towels in my cabin. "No shower? No towels in your cabin?" The blue-eyed Don, who never fails to impress Chinese people by speaking excellent Mandarin, set out to inquire. He came back with an explanation but without a towel. "When the ship leaves Xiamen for Hong Kong," he said, "all cabins have towels. In Hong Kong, the dirty towels are sent to the ship's laundry. None of the used towels are replaced. On the trip back to Xiamen, you have a 50-50 chance of getting a towel depending on whether or not your cabin was occupied on the way down."

No towel, no apologies from the state-run enterprise. The towel incident thus came to represent a certain stubborn inflexibility characteristic of Chinese socialism. "That's just the way it's done" is the attitude. Like I say, charming in small doses.

If I pushed for an explanation Don, a veteran of these incidents, says the Chinese response would probably go something along these lines:

- You're lucky there's a ship to ride on.

- You're lucky we let you on the ship.

- You should carry your own towel. Chinese hotels for Chinese people do not furnish towels. Trains furnish a clothesline that people hang their own towels on. Who are you to be so pampered?

- We do furnish towels. It's not my fault you didn't get one. Other people got one. Must be something wrong with you.

- The deputy director of the steamship line: "Your question about towels on the northbound journey on one of our steamships is being redirected to those at the appropriate managerial echelon." Translation: I don't do towels; find someone who does.

"The Beijing Zoo"

In preparation for my trip to China, I read several publications including the widely accepted Lonely Planet guidebook, which devotes nearly 100 pages to Beijing alone.Written in a folksy, opinionated style, the popular guidebook sends tourists here and there, advising of bargains and warning against rip-offs. But in at least one area I found its authors to be guilty of a totally bum steer.

A short five-paragraph section in the guidebook manages to convince any wary traveler to skip the Beijing Zoo. This is too bad, because the two afternoons I spent at the zoo were delightful.

"The Panda House, right by the gates, has four dirty specimens that would be better off dead," lectures the guidebook. "You'll be happier looking at stuffed toy pandas on sale in the zoo's souvenir shop."

"The Panda House, right by the gates, has four dirty specimens that would be better off dead," lectures the guidebook. "You'll be happier looking at stuffed toy pandas on sale in the zoo's souvenir shop."

I beg to differ. While it's true that some people will never be happy looking at caged animals, it seems to me that the Beijing Zoo is no worse - and is probably a lot better - than many others.

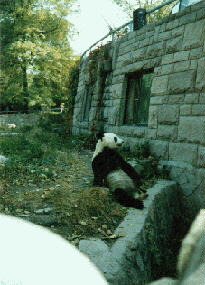

The pandas, for instance. No way I was going all the way to Beijing only to skip the pandas because they looked dirty. But I confess I approached the panda house with some trepidation. Fortunately, my misgivings disappeared in a matter of seconds.

I spent about 45 minutes watching a panda put on a show in the back yard of his cage. This was no depressed mammal. First he picked up a large stone container and played with it briefly, then he scratched himself on a tree and seemed to play hide and seek with onlookers, then he ambled into his freshwater pond and out again for more tree-scratching. The crowd laughed appreciatively at his every clownish move, the comedic effect emphasized by the animal's black eyes, round black ears and white face.

A lot of people gathered at the next cage over, too, but I couldn't tell what they were looking at until I glanced upward. There, in a skinny tree, a large lump of a black and white panda slept high in the branches, sometimes stretching out a languid foot. It looked like it might crash through the canopy at any second. The tree must have been stronger than it appeared for when I came back a few days later he (or she?) was still sleeping in the top branches.

I spent a long time, too, watching the rhesus monkeys play on their mountain. These monkeys seemed adjusted to life in the zoo. They chased each other and the ubiquitous mice, played friendly tug of war games using the impassive youngsters as rope, begged passersby for popcorn.

I spent a long time, too, watching the rhesus monkeys play on their mountain. These monkeys seemed adjusted to life in the zoo. They chased each other and the ubiquitous mice, played friendly tug of war games using the impassive youngsters as rope, begged passersby for popcorn.

The zookeepers seemed to be attentive to their charges. At feeding time, the dozen or so Arctic wolves - small silver gray animals -- went nearly hysterical as their keeper approached with a bowl of what looked like raw hamburger meat. He entered the cage and threw out balls of food, taking particular care to make sure the dark gray runt got more than his fair share of the chow.

I noticed that the signs on these wild dog cages carried a familiar symbol - a small golden arch. McDonalds has many outlets in Beijing with the biggest serving more than 10,000 people a day in a downtown three-story restaurant. It makes great public relations sense for the corporation to underwrite partial care of zoo animals. But in this case McDonalds was underwriting not the animals but only the cost of the sign, which said: "Please do not throw things at or feed the animals."

The zoo also is a great place to people-watch. With few Western tourists in evidence this fall, the zoo was full of locals doing two things they seem to like doing best: spending time with their children and taking photos of them. In China, this usually means one child per family and that child is usually a boy.

The zoo also is a great place to people-watch. With few Western tourists in evidence this fall, the zoo was full of locals doing two things they seem to like doing best: spending time with their children and taking photos of them. In China, this usually means one child per family and that child is usually a boy.

The zoo is located in the northwest corner of the city not far from Peking University. The former Ming dynasty (1368-1644) garden was converted into a zoo in 1908. Admission is only three yuan, less than 50 cents. It is home to 400 species including the rare and beautiful snow leopard. When I was there, I saw a male and a female snow leopard sleeping together on top of their hut in their outdoor cage. The looked up and blinked once in a while as if to say: "No show today."

I told several longterm Beijing visitors how much I liked the zoo and they all seemed surprised. After comparing experiences, I figured out that those who visit the zoo in the summer seem not to enjoy it. During the summer, Beijing is crowded and hot and the miserable zoo animals do little but pant in the shade. So do yourself a favor. Plan your trip to the Beijing Zoo in the spring or fall.

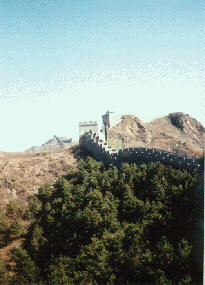

"The Great Wall"

We find a sunny corner protected from the wind and sit down, tired from hiking. I unpack sweet green tangerines, summer sausage sandwiches, raspberry cookies, bottles of still-cool water. We stretch out. This is the life.

We find a sunny corner protected from the wind and sit down, tired from hiking. I unpack sweet green tangerines, summer sausage sandwiches, raspberry cookies, bottles of still-cool water. We stretch out. This is the life.It's a late Saturday morning in October and I'm enjoying a picnic lunch in one of the most picturesque places in China - on the Great Wall.

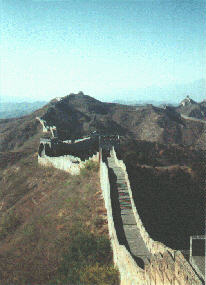

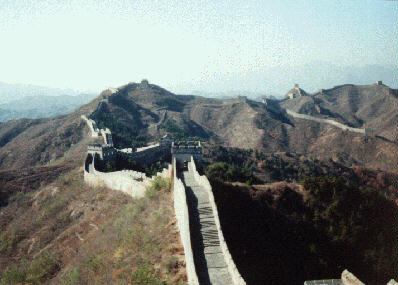

About a dozen of us have taken a private bus from Peking University to this deserted spot in the hamlet of Jinshangling 2 1/2 hours northeast of Beijing via the smooth, paved Beijing-Chengde Highway. While we're eating lunch, the rest of the group is hiking along the wall to another village. We'll go back to the bus and drive over to Simatai to meet them in a couple of hours. The hike from Jinshangling to Simatai along the Great Wall is arduous but very popular with students and day-trekkers.

In the meantime we talk, eat, and take myriad photos of the same scenes over and over again. We can't believe we're here, sitting on this wide serpentine wall curving away in front of us and behind us for miles and miles. No other tourists are anywhere near. We have the wall to ourselves. Most tourists go to the Great Wall at Badaling - an unpleasantly overcrowded tourist trap that experienced travelers avoid.

In the meantime we talk, eat, and take myriad photos of the same scenes over and over again. We can't believe we're here, sitting on this wide serpentine wall curving away in front of us and behind us for miles and miles. No other tourists are anywhere near. We have the wall to ourselves. Most tourists go to the Great Wall at Badaling - an unpleasantly overcrowded tourist trap that experienced travelers avoid.

My companions are Luo Zheng, 60, a professor of psychology and the arts who teaches at Peking University and an American student, Van Tran, 21, from UC Santa Cruz.

"I came here to study Chinese because I'm ethnically Chinese," says Tran. "I can speak Chinese, but I'm not able to read or write. I thought coming to China would be a great way to learn the language and culture and discover my ancestry. I like it a lot. The only thing I don't like are the toilets."

Squat toilets are the bane of every Western tourist's existence in China but China is changing quickly. The Chinese have discovered tourism and if it takes the installation of Western toilets to keep the tourists coming the Chinese will probably take that step.

Ironically, throughout China's history the Great Wall rarely marked the country's actual borders. Like many military projects, it came to be regarded as a massively wasteful enterprise. The Communist government faced a dilemma in how to treat the Great Wall: Should it be looked at as a national tragedy, a shameful failure and something to be destroyed or a magnificent accomplishment worthy of national pride and continuing expenditure to maintain as a tourist attraction? It finally settled on the latter, claiming the wall to be a great monument to the skill and tenacity of the common people who did the actual construction work.

Ironically, throughout China's history the Great Wall rarely marked the country's actual borders. Like many military projects, it came to be regarded as a massively wasteful enterprise. The Communist government faced a dilemma in how to treat the Great Wall: Should it be looked at as a national tragedy, a shameful failure and something to be destroyed or a magnificent accomplishment worthy of national pride and continuing expenditure to maintain as a tourist attraction? It finally settled on the latter, claiming the wall to be a great monument to the skill and tenacity of the common people who did the actual construction work.

So after 1979 when China opened its borders to the West, the Chinese began promoting the wall as a lucrative tourist attraction. It's even become a fad among foreign students and young travelers to sleep overnight on the wall - and just as quickly signs have been posted saying: "Please don't sleep in the Great Wall." Tran and several other students brought their sleeping bags but decided that it might be too cold to sleep overnight.

Tran acts as my interpreter for Professor Luo. I ask him what he thinks of the increasing number of foreign students coming to Beijing.

"I understand that many of the Chinese-American students were born and raised in another country but are coming back to their roots. That's good. But I'd like to see more Caucasian students here, too. I want more people to understand Chinese culture."

(Seventeen of the 60 University of California students studying in Beijing this year are Caucasian. The rest are either ABCs or CBCs - that's American-born Chinese or China-born Chinese.)

Professor Luo is a particular fan of Beijing opera and I tell him about a movie I saw in Beijing called "Looking for Fun." Directed by a young woman named Ning Ying, it's about a group of elderly Chinese men who form an amateur club to perform Beijing opera. Professor Luo also is a big Hitchcock fan and we talk about our favorite movies. I promise to send him a copy of "Rebecca," which I claim is Hitchcock's best. The professor says a Hitchcock movie is shown every night on Beijing TV. It turns out that the featured movie is shown nightly, yes, but in 30-minute segments.

Professor Luo says he's had opportunities to study and teach in the United States but has never been able to go because he and his wife care for his aged parents.

"I believe China will dissolve communism and move in the direction of the United States," he says. "After Deng dies China will change more, but whether that will be a big or small change it's hard to say."

The professor wonders how much it would cost him to visit the United States. He makes less than $100 a month but pays practically nothing in rent since housing is provided by his work unit. And he doesn't have a car. But he is still poor even by Beijing standards where a taxicab driver makes about $350 a month.

I shake my head. I can't imagine he'll ever have enough money to visit the United States.

The wind gusts as we finish our lunch and begin hiking back down to the village below and the waiting bus.

"Isn't it beautiful?" the professor asks.

"It's magnificent," I say.